Quang Ngai, January 2020.

Jim wanted to go. I was only six when it happened. Son My had no place in my consciousness. Jim was eighteen. ‘I was angry at the Americans, angry about the war. I can’t be so close and not go’, he told me. So I went – because he wanted to, and maybe to learn something.

We hired bikes and cycled. Close to the river on a three lane highway. The highway was so new that no-one was using it yet, so we cycled in peace, the odd motorbike passing, still tooting away, although there was no need. We could have been in the countryside, surrounded by rice paddies and vegetable plots as we were, and momentarily a picture-book wooden stilted bridge on our right. We noticed photographers, surely they weren’t taking pictures of us? Before we had time to think the procession was upon us – a newly married couple on a motorbike, the bride sitting sideways, carrying her cake in front of her, bridesmaids and males coupled on bikes behind. They all waved, all shouted hello, and laughed. We were right in the middle of it, and will be forever in their photographs.

We reached the village. I went to learn something but I’m not sure I did. Like the photographers it was a puzzle. The site was beautiful, tranquil, full of colour, scented flowers and palms swaying in the breeze. Silence. We were alone. We listened. You might think the earth would stop spinning after such a thing, but it does not. A disaster for one does not register with another.

House foundations remain, names of family members noted neatly on plaques. Old people. Or children younger than I was at the time. The Americans claimed it was a Viet Cong village, but men between twenty and thirty feature nowhere in lists of the dead. One house has been restored; beds and a dresser, pink lotus flowers and yellow bananas against a grey concrete wall. An old woman prepares breakfast for her grandson in an outdoor kitchen, the cow grazing in a wicker enclosure close by. It takes me a fraction of a second to realise that they are mannequins but even so I feel compelled to place my hand on the head of the boy. To let it rest there. He is not real, but I’m sure the dead feel my energy and intention.

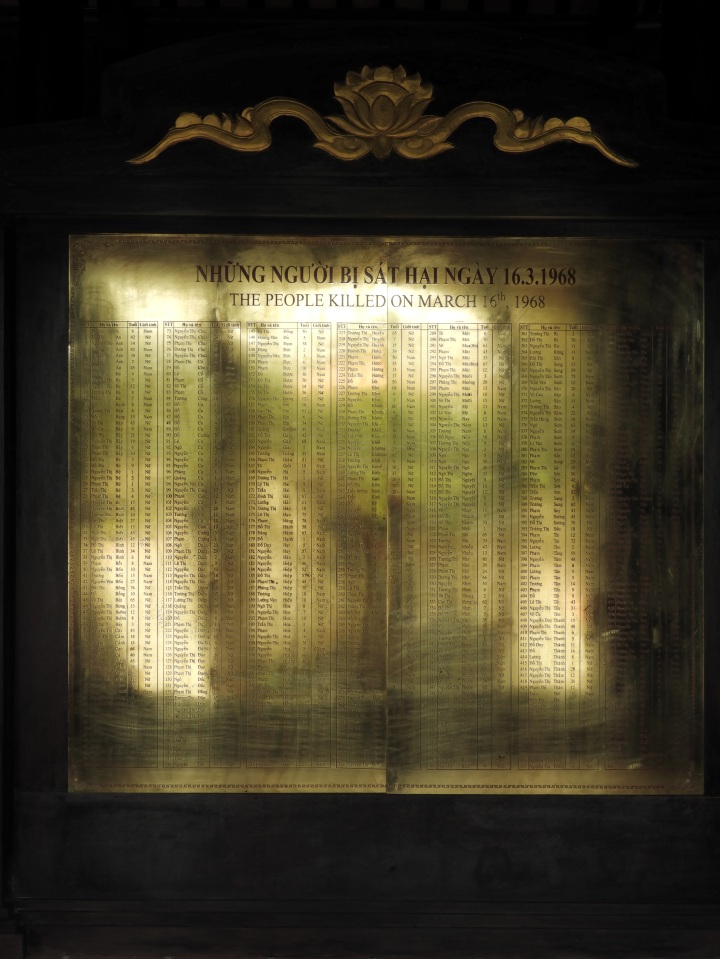

At about 07.30am on 16 March 1968 the US Army’s Charlie Company landed close to Son My. They encountered no resistance and did not come under fire at any time during the operation. The museum shows an American military photographer’s graphic photographs of what happened next. A seventy-two year old man thrown down a well, a hand grenade after him. A small group of women and children clustered together under a tree. A child’s face creased with tears and fear. Two boys lying dead on a dirt track, the older brother curled protectively around the younger, trying to shield him from what was to come. Between seventy-five and one hundred and fifty villagers were herded to a ditch, where they were executed by machine gun fire. Livestock was slaughtered, dwellings and crops burned, girls and women gang raped.

Words do not, cannot, convey the terror, noise, fear, and devastation. The brutality. The pain. The suffering. The violence. Why? was the question that burned. Son My was almost certainly not the only massacre. Outrages occur constantly during war. The museum – perhaps understandably – makes no attempt at understanding. But we did as we sat looking at the memorial. That was the only way we could deal with the enormity of it.

The Americans were fighting an elusive, seemingly invisible enemy, one that injured and killed by stealth. Charlie Company had suffered twenty-eight casualties involving mines or booby-traps; one just two days before the massacre when a popular sergeant was lost to a land mine. The enemy were supported by villagers like those living in Son My – all Vietnamese were therefore suspect. ‘They’re all VC, now go and get them’, Ernst Medina (Captain of Charlie Company) reportedly told GI’s at the briefing.

When I laid my hand on the head of the dummy boy I wanted to tell him ‘I’m sorry’. What I meant was ‘I’m sorry for us all’.

Difficult things should not be avoided. I am glad I went to Son My. I cannot say why. It just felt right.

My dad and I watched the Ken Burns series about the war, all ten episodes (18 hours). Some of the interviews are quite moving, both American and Vietnamese. One of the episodes covers Mỹ Lai (Sơn Mỹ).

LikeLike

Thank you. I will see if I can find this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your emotions and passion come through beautifully in this post. Thanks for sharing all, but especially the statue that will stick with me. Very powerful.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments. It was a very intense and extraordinarily moving place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a heartfelt and sad, yet well-written post, Trace. The Americans have messed up many countries and that becomes all too clear when you travel a lot, especially in Central America. How I would hate war! Much anger and unfairness on top of the “usual” killing… 😦

LikeLike

I think all old colonial powers have messed a lot of places up – not just America. The Corona situation has given me a very small insight into what it must be like to live through a war in the sense of life being on hold, uncertainty and fear.

LikeLike

what a moving experience – thanks so much for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

We are a sad cruel blundering lot aren’t we 😦

I must be closer to your husbands age, older actually. The war in Vietnam was a very real part of my early 20’s and I attended many protest marches in Australia back in the early 70’s until finally they ended it. There was no reason for it to happen at all. The “reasons” given were specious, but were probably far more about the military-industrial machine making money than anything else. I too was angry. And sad. So much cruelty and pain.

Thank you for your thoughtful writing about it. I can’t bring myself to call it the Vietnam War. To the Vietnamese it’s known as the American War. And so it was.

Alison

LikeLike

I understand all your feelings about this. It was really a terrible thing. Still having an effect on so many people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You write a poignant post on this time in history that was filled with so much senseless tragedy and death … We were very aware of it all while we were in Viet Nam, especially after we visited the museum in Saigon which contains so many disturbing and powerful images and descriptions of what happened.

As Alison pointed out, the Vietnamese call it the American War and rightly so. For sure for me, one of the most eye opening aspects of travel in SEAsia is that I have learnt so much about the tragic histories in every single country we were in. I was not a good student as a teenager, but besides that, being in the place where history has happened is such a powerful way of learning and getting just a glimpse into how events have shaped a country and a people.

Peta

LikeLike

That’s one of the things I really love about travelling, Peta, – the chance to learn, and to learn in such a way that whatever it is, makes an impact. It has so much more staying power, and power to move than any learning from a book. We too came across evidence of how the war had affected people time and time again during our trip to Vietnam.

LikeLike

Tracey, it was a terrible time and you’ve captured the immense sadness and anger that were pervasive in those days – both abroad and at home. We watched family and friends march off to war – some to never be seen again. When we visited Southeast Asia we felt the weight of all the awful decisions that were taken. Thanks for writing such a powerful post. ~Terri

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment Terri. Much appreciated.

LikeLike